|

So it’s not a developmental edit? No. It’s not. While developmental editing does look at language as a function of the entire manuscript, its primary focus is on larger structural functions of the story like timeline, pacing, character development, and authenticity. Developmental editing is taking a macroscopic look at the book, while line editing is applying a mesoscopic (middle or intermediate) lens to the content. And it’s not a copyedit? Nope again. Copyediting is the final microscopic lens of editing. Copyedits correct errors in spelling, punctuation, grammar, fact-checking, word usage, and style. A copyedit wants consistency, and it seeks to eliminate glaring language errors that will distract readers and pull them out of the story. What might a line edit look like? There might be some elements of both developmental editing and copyediting involved in a line edit, especially because the goal of this type of edit is to upgrade the language for clarity. A reader will not achieve that blissful feeling of sinking into your text if it has glaring inconsistencies. So along the way, line editors will likely address any or all of the following elements:

Why is it important to know the difference? You might be looking to hire a freelance editor for a manuscript, and they’ll likely be versed in a wide variety of editorial services. You need to know the right one to select for your manuscript and how to most effectively communicate your desires. Of course, any freelance editor worth their salt is going to help you select the right service from the get-go, but arming yourself with knowledge even before approaching a contract is highly suggested. Or, if this is your first time stepping into the publishing world with a manuscript, folks are going to be using these terms to inform you of the next steps in their process. And once any type of editing is done, it’s up to the author to incorporate, apply, or revise. Some edits are much more time-consuming than others, and line editing falls into that middle territory. You’ll need to parse through all the individual edits, but it’s not nearly as complicated as a developmental edit. On the other hand, you likely won’t just be clicking “accept all” for all the spelling and punctuation errors to be magically fixed. You’ll want to investigate each line edit, and it might even require some work on your end. Conclusion The ultimate goal of a line edit is not only to elevate the manuscript, but also to improve the craft of the writer. A writer cannot address their tics if they can’t see them. They won’t know about the potential power of certain words or phrases until someone looks at their writing and points these things out. All editing seeks to improve a manuscript, but line editing in particular has the ability to have a long-lasting effect on writers themselves. This was written for and originally appeared on the Ooligan Press blog on May 11, 2020.

1 Comment

Since I'm graduating from Portland State University this weekend with an MA in Book Publishing during a time of social revolution, I wanted to share with everyone my final research paper (not a thesis, but close enough) that was based around understanding the role authenticity readers play in the editorial process and how to best incorporate them into Ooligan Press. The role of an authenticity reader (re: sensitivity reader, targeted beta reader) is often controversial for many reasons, but I want to underscore the reason that I believe their work is so crucial: they augment authenticity within manuscripts and reduce the perpetuation of harmful negative stereotypes that directly impact marginalized communities. I do not believe that authenticity readers are THE solution to the inequality in book publishing, nor do I believe they are a band aid solution. I believe they are a tool that both authors and editors should incorporate into their processes as a crowd-sourcing method of fact checking, especially fictional content. If authors are writing outside of their own lived experiences, they need to do their research. They need to do A LOT of research. If editors are acquiring "diverse" books that are not Own Voices, they need to do their due diligence and ensure that these manuscripts are not actively harmful to depicted communities. In both cases, writers and editors need to ask themselves if the writer is the best person to tell that story. Writers need to be critically examining whether they are occupying space in the industry that could otherwise be allocated to a BIPOC or a member of the LGBTQ+ community or someone with that lived experience. It is a moral question and it is one that we should absolutely be asking ourselves every time we sit down to write. This doesn't mean you have to stop yourself from writing. But it does mean you need to be highly aware of the optics and the privilege of trying to get that work published. You can write whatever you want. But the publishing industry is a cultural medium and representation in the industry matters. It always has. Own Voices is another tool to clear out space for marginalized voices in the publishing community, a more powerful and effective tool than authenticity reading. In my opinion - the controversy around this aspect of the editorial process is manufactured. Authenticity readers are not cultural gatekeepers because acquisitions editors and publishing houses and marketing departments already do that work. The perceived threat lies solely in the idea that marginalized communities might actually get A VOICE in the process and that it might be corrective to white, cis-hetero authors who dominate the market share of the industry. The threat is a perceived one and it exposes another ugly layer to the truths that have been unveiled over the last few weeks as the Black Lives Matter movement has gained national and global prominence. White supremacy is systemic and authenticity readers and BIPOC editors and writers threaten the power of that system. But the use of authenticity readers is not just about Black representation. It's about representation as a whole and the goal is to provide another system of fact-checking for accuracy in depiction, especially in the current framework where we have a dearth of editors of color actually employed in the industry, and a wealth of dominant paradigm writers seeking to incorporate greater diversity into their manuscripts. Abstract Authenticity readers have been utilized at publishing houses and by authors for a decade or more, but their role is arguably growing more controversial. Why is that? Authenticity readers have influence over manuscripts, but they aren’t editors. So what is their ultimate role in the editorial process? Through interviews with authors and editors, as well as a survey of 72 publishing professionals, and an ethnographic case study at Ooligan Press, this research paper seeks to determine where in the editorial process sensitivity/authenticity readers should be involved and how authenticity readers influence the overall editorial process. The result of the collected data is that manuscripts featuring communities that are not part of the authors lived experience should undergo authenticity reads in order to more accurately depict those cultures or communities. The reads should happen before or during the developmental edit. Both authors and editors should take part in employing authenticity readers, and it is suggested that multiple authenticity reads take place. Authenticity reading is not prescriptive, and individual authenticity readers are not wholly representative of their communities. Authenticity readers should not censor a manuscript, nor should they be used to shield it from criticism. Their role is purely to vet a manuscript for inaccurate or stereotypical portrayals. The data compiled in this research was used as the basis for moving forward with formalizing the authenticity reading process for Ooligan Press and developing a database of PSU students and alumni to serve as volunteer readers for future acquisitions.

I knew I wasn't ready. I knew it wasn't the right time. I'd JUST finished up the long road to completing my MA Book Publishing thesis and the accompanying oral exam last Friday and was staring down the barrel of an agent first 5 pages evaluation on Saturday morning that I'd signed up for MONTHS ago during happier times with stars in my eyes and more hope for the world.

I knew it wasn't going to go anywhere. I could tell the night before. I could tell when I woke up that morning and felt my guts already twisted up in knots. I was not mentally, emotionally, or spiritually in the right place to go forward with this manuscript evaluation but I'd already paid $50 so I gamely put on a blazer and red lipstick and posed myself in front of a virtual bookcase in the middle of my untidy living room for 14 minutes of feedback that was akin to drinking poison. The strangest part is that I smiled and laughed and repeated the phrase "that's fair" to this agent over and over again without the slightest indication that they were cutting me deep with their words. I've never had this extra power of looking at my own face while my poor little artist heart was being broken and the impact of staring into my own eyes during an agent evaluation was profound. When I finally shut the lid of my laptop and immediately set to the task of deep cleaning the bathroom, I replayed those moments over and over again and the biggest noise in my head, besides the cranky whirring of the bathroom fan, was "I paid for this shit?" And I wasn't talking about the toilet. I am wrapping up 18 months of deep diving into the publishing industry (ostensibly now, a master) and I just need to remind my fellow writers of something... Agents need us. Publishers need us. Editors need us. The entire publishing industry needs writers to submit their work. They truly do. Without writers, there is no content to push. There are no agents. No editors. No publishing industry. And it goes beyond that. Agents and publishers aren't just acquiring our content. They're acquiring our networks. They're looking at our social media presence and backgrounds and pondering just how many people are in our contact lists. They don't just need our work. They need our personhood, our authority to tell and sell this story. And, if you look at the writing conference industry of which I am a willing participant, it looks like they also need our money. Writers dump SO MUCH MONEY into their craft, into writing communities and workshops and MFA programs across the world and into the publishing industry. And yet somehow, SOMEHOW, there's this constant background chatter that WE are wasting other people's time. That other people's time in this industry is almost always inherently more valuable than ours and we should be paying for the privilege of their time. Because there are so many writers out there and any one of them could fill our shoes and, and, and...OK, let them. They gotta do what they gotta do. Everyone does. But for me, especially right now when so many things have been thrust into stark relief, I have to look myself in the eyes. I am forced by circumstance to stare in a digital mirror and be accountable to myself for what choices I make and what things I perpetuate in the publishing industry by participating in them. I am done paying agents for their counsel. In fact, the bigger reveal is that I knew I was done paying agents before I even had that fateful meeting. I knew I was done earlier last week, when I registered for a writing conference and had no desire or motivation or interest in signing up for an agent evaluation. There are others ways I need to spend my time that will boost my craft AND grow my contact list AND allow me to create content. The possibilities are almost dizzying. And if I look myself in the eyes while doing any one of those things, I don't think I'll wince inwardly and feel the need to tell myself, "you deserve better." Not at all. Technically, it's a "final research paper" but part of my Book Publishing masters program is to complete a research paper VERY similar to a thesis, that entails doing some kind of data collection. I've chosen to do both surveying and interviewing to collect data on how writers and editors employ authenticity readers and how they help shape the editorial process. So far I've received a couple dozen responses, but my goal is to get at least 100 survey responses before April 24, 2020.

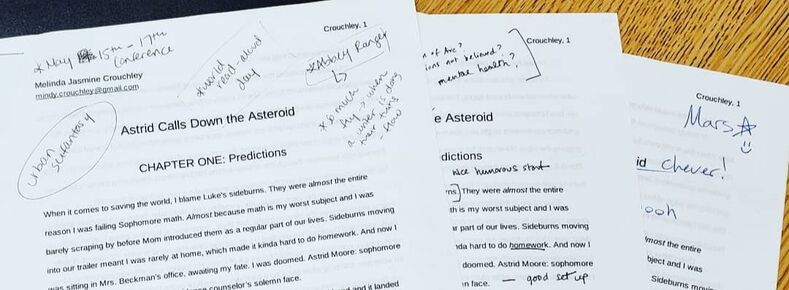

The survey link is here: https://forms.gle/JNtTJgxsa9jkg9eU7 The big question: How do authenticity readers impact the editorial process of a manuscript? If you’re an author, editor, publisher or authenticity reader in the book publishing industry please consider taking this survey to help gather data for a graduate thesis in the Portland State University Book Publishing program. The paper is seeking to understand the ways in which authenticity readers are employed in the editorial process, by whom they are most commonly employed within the industry, and how their inclusion helps shape the overall editorial process of a manuscript. Personal information in the survey will be kept confidential. Interested parties can also indicate if they’d like to participate in a short interview with some expanded and more detailed questions, along with completing a consent form. This survey will close on Friday April 24th, 2020. All survey participants who include their emails will be entered into a random drawing for a $10 Powell's e-Gift Card. Please share this survey with your networks in the book publishing industry and help spread the word. This past weekend I attended my second EVER structured critique with the Oregon Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators. It was an especially intense round because the YA Author leading the critique, Suzy Vitello, is also now an Ooligan Press author. We recently acquired her speculative fiction novel set in Portland, Oregon and I had the pleasure of participating in the developmental edit of the manuscript.

THE DEVELOPMENTAL EDIT I specifically focused on the structure of Suzy's manuscript and built out a table that tracked the entire timeline of the book, breaking down each chapter into setting, characters, and actions. And you better bet I added some color details. I didn't go quite as bold with the colors, in the way that I would with my own material, because I wanted the focus to be on the written content of the table. I knew as soon as I registered for the Winter Great Critique and saw Suzy's name among the participants that this was an experience that would be incredibly valuable. I'd edited her work and she'd recently received the note, so it seemed especially fitting that she would in turn provide critical feedback on the first five pages of Astrid Calls Down the Asteroid. THE GREAT CRITIQUE I fully did not expect Suzy to bring a copy of the timeline table to our critique group. Of course I showed up late so our re-introduction (we first met at the Willamette Writers conference in August 2019) didn't take place until the mid-point break of the workshop. At our circled table, she had a stack of papers and when I mentioned that I'd participated in the developmental edit, she showed the table to me. It was such an awe-inspiring moment to witness the writing cycle to come full circle. My editing experience has helped me as a writer, which helped Suzy as an author, which has benefited Ooligan Press, and now she has helped me improve my own writing by providing critical feedback about the opening pages of my newest manuscript. BETA-READERS Another special bonus is that one of the authors at our table was, in fact, a YOUNG ADULT and her feedback around the authenticity of our teens voices, experiences, thought processes, and behaviors was so incredibly valuable. It made me realize that in my beta reading I've been largely missing one critical element to help guide my revision process: the insight of a teenager. Teen readers are especially welcome, but having a teen author who understands the sensitivity of the critique environment was especially important. WHAT NEXT? Suzy reached out to me post-class and has passed along the timeline table method to the Author Accelerator program to share more widely with the writing community. If you're interested in seeing an example of the timeline table (with information changed to protect Suzy's original work) then please feel free to reach out: melinda.crouchley@gmail.com. I'm also ready to start scheduling out freelance developmental and content editing services for post-graduation so if you're interested, please get in touch: melinda.crouchley@gmail.com. I'm pleased to announce I will be co-leading an Editing Seminar at the 2020 Write to Publish conference hosted by Ooligan Press and the Book Publishing program at Portland State University. My current position is Managing Editor at Ooligan Press and even though I only started my book editing journey in 2018 and have edited precisely 14 books total thus far, I've been editing my own personal manuscripts and been in marketing and communications and editing roles pretty much my entire life.

I'm very excited to share both my professional knowledge and my personal experience around the craft of editing, and hopefully inspire and inform writers to choose whatever style of editing is most appropriate for their manuscripts. And it's not just me filling the void. Des Hewson, the current Acquisitions Editor at Ooligan Press, and a former professional copyeditor will be co-leading this panel. Very hyped for them to share their experience when it comes to real world editing. The Write to Publish conference will take place on January 11, 2020 from 9am-5:30pm at the PSU Smith Student Union building and will feature a wide variety of panels specifically geared towards writers who are interested in being published through traditional means, as well as offering self-publishing tips and tools. The editing seminar will focus on teaching the basics of editing, will briefly review the editorial process at Ooligan Press, and will likely feature an editing exercise plus a brief Q&A session. The seminar will take place from 3:45-4:45. Conference registration is open now. We hope to see you there! Approaching the 2019 Nanowrimo while juggling two part-time jobs and full-time grad school (plus motherhood but who's counting) meant that I had to make some realistic choices. Could I expect to write anything new in 30 days, especially 50k words worth of something new?

No. Not really. BUT I could put to practice some of the sweet developmental and copyediting skills I've gained over the last year in the Book Publishing MA program at Portland State University. So my goal became simple: cut 50k words from a bloated 150k manuscript instead. The bloated manuscript in question is Tin Road. The first step in downsizing or upsizing is to know what you're working with. Since I typically don't write from highly structured outlines (I use a very rough outline and take notes in the same document as I write), I had to reverse engineer an outline based on the current material. I crafted a table, listed out the chapters, gave them breezy subtitles, and loosely described each chapters content. Then I color-coded. So much color coding. I love a good color based organizational system. I used yellow and red because they're bold and bossy. Yellow was like "this chapter could be trimmed" and red was like "probably could cut this entirely." There weren't nearly as many red rows as I'd hoped, which meant the harder job of making line by line cuts. But also, at the same time, cleaning up the content. I did get to hack away at cringe-worthy scenes or moments that just weren't feeling good. ONE PIECE OF ADVICE. If the writing doesn't feel good, if it makes you cringe, then it's not good and you should cut it without mercy. Your gut instincts are always on target. I did some gut cuts , as well as trimming dialogue. DIALOGUE CAN ALWAYS BE TRIMMED. No reader needs a "yeah" or "well" to kick off a sentence and no reader needs nearly as much blocking or descriptions in the dialogue as you think they do. I even found myself dispensing of dialogue tags altogether in favor of trusting a reader would know who was speaking based on voice and placement in the scene. Kinda tricky and scary, but worth it to step out of the way and let the characters talk to one another without leaning back on blocking. Plus, it dropped my word count considerably. BYE BYE EXPOSITION. Part of the book is following the journey of two fugitives. It's a road book, and that meant a lot of logistics plotting and descriptions of new environments. Which is where a lot of the bloat was located. Who needs three pages of describing a location that is only gonna be used to stage about two minutes of action? Cut cut cut. SCENE IT BEFORE. And sometimes there is a scene that's almost exactly like another scene except the characters are maybe saying different things. Is it needed? Could the dialogue be moved elsewhere? Good riddance then. THE END RESULT. Not as successful as I hoped, but for a couple of reasons. I fell about 20k words short of my lofty goal, which was a bummer. HOWEVER, I did emerge with an entirely edited and fairly clean copy of a manuscript that was reduced by 20% (maybe, I don't math well). AND keeping the 120k words made sense in light of the fact that I had two narrators telling different stories (interwoven, but still). That was roughly 60k words per narrator and story which is lean. If I cut anything else, it might end up causing both tales to be anemic. AND NOW. I'm giving it a final once-over and then formatting it to be entered into the Smashwords catalog and then the 2019 Multnomah County Library Writer's Project contest by the 12/15 deadline. Wish me luck. Regardless of its acceptance into the contest/catalog, I plan to make Metal Heart and Tin Road available for ebook and print this upcoming year. |

AuthorMelinda Jasmine Crouchley, YA supernatural science fiction author and professional editor. Archives

February 2023

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed